Pet Owners

Specialties & Services

With more than 20 specialties and services under one roof, the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center is able to provide high quality collaborative care.

Find A Doctor

The Schwarzman Animal Medical Center is dedicated to providing the highest quality medical care. Search our world-renowned staff by name, department, or condition.

Search Now

About Your Visit

Get ready for your visit to AMC with important information on parking, renovations, and hospital policies.

Learn More

Financial Assistance

Compassionate care is at the core of AMC’s mission, and we offer a variety of financial assistance programs based on need and eligibility.

Learn More

Our Blog

Written by staff oncologist and internist, Dr. Ann Hohenhaus, AMC’s weekly blog is an engaging and educational resource for pet owners looking for pet health tips and information.

Learn More

Ask the Vet Podcast

In partnership with Sirius XM, the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center presents ‘Ask the Vet,’ a podcast all about the pets we love and how to care for them. Dr. Ann Hohenhaus answers questions for pet parents, chats with leading animal experts, and talks about the most concerning issues for our furry friends.

Learn More

Pet Stories

Pet stories showcases the remarkable spirit and courage of AMC’s patients and those who care for them.

Learn More

Social Work Services

AMC is committed to supporting the human-animal bond. Veterinary social work services can help you and your family cope with the challenges of caring for your sick or injured animal companion.

Pet Loss Support Program

Learn MorePet Loss Support Resources

Learn MoreAbout Social Work at AMC

Learn MorePet Caregiver Support Group

Learn MoreAbout the Usdan Institute for Animal Health Education

The Usdan Institute for Animal Health Education at AMC is the leading provider of pet health information.

Learn MorePet Health Library

Your A-to-Z guide to common conditions, clinical signs, and wellness tips.

Learn MoreEvents

The Usdan Institute hosts free, monthly events for pet owners and the public. Attend an upcoming event or stream previous events.

Learn MoreVeterinary Community

Specialties & Services

With more than 20 specialties and services under one roof, the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center is able to provide high quality collaborative care.

Referral Form & Procedures

Access all of the information you need to refer your patients to the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center.

Learn MoreReferral Coordinators

AMC’s Referral Coordinators work with referring veterinarians to ensure coordinated patient care and communication before, during, and after all consultation appointments and procedures.

Learn MoreSend & Receive Medical Records

To ensure optimal patient care, AMC makes it easy to share medical records with our specialty services.

Learn MorePostgraduate Education

The Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Institute for Postgraduate Education features comprehensive curricula including our Externship Program, Internship Program, and Residency Program.

Learn MoreContinuing Education

As part of our ongoing commitment to education, the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center hosts regular lectures and conferences led by the top minds in veterinary medicine.

Learn MorerDVM Newsletter

Sign up for our rDVM newsletters to stay up to date with the latest news and clinical guidance from AMC’s staff.

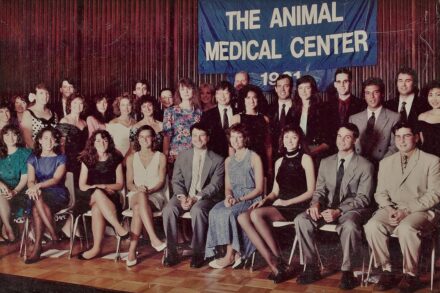

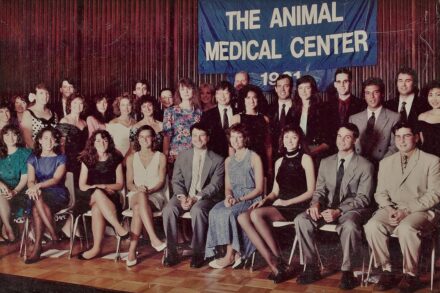

Learn MoreAlumni Relations

Since 1964, thousands of veterinarians have graduated from AMC’s postgraduate education programs. We’re immensely proud of the wide ranging achievements and contributions of our alumni.

Alumni Relations

Research

The advancement of veterinary knowledge is central to the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center’s mission, and our staff regularly undertakes pioneering research to make sure we’re able to provide the best possible outcomes for our patients.

Clinical Trials

For more than 50 years, AMC has conducted clinical trials to contribute new scientific knowledge and improve the medical and surgical care for animals.

Learn More2022 Publications

As a leading veterinary research institution, AMC residents and faculty conduct cutting-edge research to advance the care and treatment of our beloved animal companions.

Learn More2023 Pet Holidays and Veterinary Awareness Days

Public education is one of AMC’s founding principles and an enduring mission. Use this calendar to spread awareness of common pet health topics among your veterinary clients, colleagues, family, and friends.

Learn More

Supporters

Our Impact

We’re able to do amazing things with the support of our donors. Take a look at the impact you make with your donation to the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center.

Learn More

Community Funds

AMC’s Community Funds assist animals whose owners are unable to afford either basic or lifesaving specialty care, as well as rescue animals, guide dogs, and retired police and military dogs.

Learn More

Get Involved

Your support of the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center promotes the health and well-being of our animal companions through comprehensive treatment, research, and education.

Donate Today

Learn MorePlanned Giving

Learn MoreDonor Recognition Societies

Learn MoreMore Ways to Support AMC

Learn MoreDonor Honor Wall

The Schwarzman Animal Medical Center extends its deepest gratitude to our committed and loyal supporters who enable us to provide compassionate care and train the veterinary leaders of tomorrow.

Learn More

Attend an Event

The Schwarzman Animal Medical Center hosts regular events in the New York City area. Join us to connect with other pet owners, our veterinary community, and learn more about your pet’s health and well-being

Learn More

Donate Today

As a non-profit institution, AMC’s success is dependent in large part on the generous contributions of donors like you.

Donate

A Gift of Love

By adding more than 11,000 square feet of new construction and renovating more than 26,000 square feet of existing space, the Gift of Love campaign will transform the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center.

Learn More

New York, NY 10065 Contact Us

Pet Owners

CloseSpecialties & Services

Find A Doctor

Find A Doctor

The Schwarzman Animal Medical Center is dedicated to providing the highest quality medical care. Search our world-renowned staff by name, department, or condition.

Search Now

About Your Visit

About Your Visit

Get ready for your visit to AMC with important information on parking, renovations, and hospital policies.

Learn More

Financial Assistance

Financial Assistance

Compassionate care is at the core of AMC’s mission, and we offer a variety of financial assistance programs based on need and eligibility.

Learn More

Our Blog

Our Blog

Written by staff oncologist and internist, Dr. Ann Hohenhaus, AMC’s weekly blog is an engaging and educational resource for pet owners looking for pet health tips and information.

Learn More

Ask the Vet Podcast

Ask the Vet Podcast

In partnership with Sirius XM, the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center presents ‘Ask the Vet,’ a podcast all about the pets we love and how to care for them. Dr. Ann Hohenhaus answers questions for pet parents, chats with leading animal experts, and talks about the most concerning issues for our furry friends.

Learn More

Pet Stories

Pet Stories

Pet stories showcases the remarkable spirit and courage of AMC’s patients and those who care for them.

Learn More

Social Work Services

Pet Health Resources

Veterinary Community

CloseSpecialties & Services

Referrals

Education

Alumni Relations

Alumni Relations

Since 1964, thousands of veterinarians have graduated from AMC’s postgraduate education programs. We’re immensely proud of the wide ranging achievements and contributions of our alumni.

Alumni Relations

Research

Pet Health Holidays 2023

2023 Pet Holidays and Veterinary Awareness Days

Public education is one of AMC’s founding principles and an enduring mission. Use this calendar to spread awareness of common pet health topics among your veterinary clients, colleagues, family, and friends.

Learn More

Supporters

CloseOur Impact

Our Impact

We’re able to do amazing things with the support of our donors. Take a look at the impact you make with your donation to the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center.

Learn More

Community Funds

Community Funds

AMC’s Community Funds assist animals whose owners are unable to afford either basic or lifesaving specialty care, as well as rescue animals, guide dogs, and retired police and military dogs.

Learn More

Get Involved

Donor Honor Wall

Donor Honor Wall

The Schwarzman Animal Medical Center extends its deepest gratitude to our committed and loyal supporters who enable us to provide compassionate care and train the veterinary leaders of tomorrow.

Learn More

Attend an Event

Attend an Event

The Schwarzman Animal Medical Center hosts regular events in the New York City area. Join us to connect with other pet owners, our veterinary community, and learn more about your pet’s health and well-being

Learn More

Donate Today

Donate Today

As a non-profit institution, AMC’s success is dependent in large part on the generous contributions of donors like you.

Donate

Capital Campaign

A Gift of Love

By adding more than 11,000 square feet of new construction and renovating more than 26,000 square feet of existing space, the Gift of Love campaign will transform the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center.

Learn More